How do you know the Bible is true?

»How were the books of the Bible selected and compiled?

»What was the process the church councils went through in deciding what manuscripts would be included in the Bible? What criteria did they use in deciding which books to put into the Canon?

»We talk of the Bible as being the inspired Word of God. Would the men who chose the books to be included in the Bible also have been inspired by God?

»How does the resurrection of Jesus validate the authority of the New Testament Scriptures?

»How can we know that the Bible is the true Word of God after so many interpretations?

»Why do Christians—people filled with the Spirit of truth—disagree about what the Bible says?

»There are so many different interpretations of what the Bible is saying. How do I know which one is right?

»When I discuss biblical concepts with my friends, I’m often met with the reply “That’s your interpretation.” How should I respond?

»I recently obtained a copy of The Message arranged for daily Bible readings. Do we need to be wary of this version?

»Does the Bible claim authority over the life of a believer?

»Does the Bible claim authority over the life of an unbeliever?

»What can a Christian learn from the Old Testament? Is it as pertinent to my growth as the New Testament is?

»How does the Old Testament apply to Christians today?

»What should Christians think about evolution?

»Does the Bible tell us how old the earth is?

»As a Christian educator, what are some of your frustrations in your efforts to teach the Word?

»How do you know the Bible is true?

That’s an excellent question because so much is at stake in the Christian faith in terms of the truthfulness of Scripture. The Bible is our primary source of information about Jesus and about all of those things we embrace as elements of our faith. Of course, if the Bible isn’t true, then professing Christians are in serious trouble. I believe the Bible is true. I believe it is the Word of God. As Jesus himself declared of the Scripture, “Your word is truth.” But why am I persuaded that the Bible is the truth?

We need to ask a broader question first. How do we know that anything is true? We’re asking a technical question in epistemology. How do we test claims of truth? There is a certain kind of truth that we test through observation, experimentation, eyewitness, examination, and scientific evidence. As far as the history of Jesus is concerned, as far as we know any history, we want to check the stories of Scripture using those means by which historical evidence can be tested—through archaeology, for example. There are certain elements of the Scripture, such as historical claims, that are to be measured by the common standards of historiography. I invite people to do that— to check it out.

Second, we want to test the claims of truth through the test of rationality. Is it logically consistent, or does it speak with a “forked tongue”? We examine the content of Scripture to see if it is coherent. That’s another test of truth. One of the most astonishing things, of course, is that the Bible has literally thousands of testable historical prophecies, cases in which events were clearly foretold, and both the foretelling and the fulfillment are a matter of historical record. The very dimension of the sheer fulfillment of prophecy of the Old Testament Scriptures should be enough to convince anyone that we are dealing with a supernatural piece of literature.

Of course, some theologians have said that with all of the evidence there is that Scripture is true, we can truly embrace it only with the Holy Spirit working in us to overcome our biases and prejudices against Scripture, against God. In theology, this is called the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit. I want to stress at this point that when the Holy Spirit helps [p. 61] me to see the truth of Scripture and to embrace the truth of Scripture, it’s not because the Holy Spirit is giving me some special insight that he doesn’t give to somebody else or is giving me special information that nobody else can have. All the Holy Spirit does is change my heart, change my disposition toward the evidence that is already there. I think that God himself has planted within the Scriptures an internal consistency that bears witness that this is his Word.

The only way that the resurrection of Jesus can validate the authority of the New Testament Scriptures is indirectly. Some New Testament authors claim that what they are writing is not composed out of their own insight, but is actually written under the supervision and superintendence of the Holy Spirit. That is a radical claim to truth that requires some form of verification for most people.

The only way the Resurrection would verify the Scriptures is this: The Resurrection validates Jesus. The Resurrection, as the New Testament claims, shows Jesus as one who does miracles and is seen to be vindicated as an agent of revelation by the very fact that God gives him the power to perform these miracles.

For example, Nicodemus came to Jesus and said,

Nicodemus was thinking soundly at that point. His line of reasoning went like this: He couldn’t conceive of God granting the power to perform bona fide miracles to a false prophet. The very presence of miracles indicated the authorization of what we would call the credit of the proposer. It showed God’s endorsement of this particular teacher.

No higher endorsement could have been given than that Jesus was raised from the dead and vindicated and shown to be the Son of God, whom he claimed to be—fulfilling the very predictions he had made. In Acts, Paul makes the statement that God has proven Jesus to be the Christ through the Resurrection. What does that have to do with the Scripture? If indeed Christ is proven by resurrection to be the Son of God and then we discover that Christ, who is the Son of God, a prophet of God, a true teacher verified through the miracle, teaches that the Bible is the Word of God, then his verification of the Bible is what verifies the claims of the apostles.

The only way we know of the resurrection of Jesus is through the Bible. If the resurrection of Jesus proves Jesus, and Jesus proves the Bible, how do we get to the resurrection of Jesus except through the Bible? We don’t have to have an inspired Bible to be persuaded of the evidence of the historical activity of the Resurrection. I don’t believe in the Resurrection because an infallible Bible tells me about a resurrection. I believe that the Bible is infallible because the Resurrection authenticates Jesus as an infallible source about the Bible.

»The multiplicity and variety and even contradictory interpretations of Scripture really have little or nothing to do with the question of its origin. Let me give you an analogy.

We’ve seen all kinds of interpretations of the United States Constitution, but even though political parties and different judges have different views of what the Constitution says and means, and what it intended, none of that difference of opinion casts a shadow on the source of the Constitution. We know who wrote the Constitution. We know where it came from and what it is.

People get dismayed by the differences of opinion as to what the Bible teaches. If we establish that the Bible is the Word of God, only half the battle is over. The next thing we have to figure out is, What does it say? Can we agree on what it teaches? The assumption is, if I can convince you that what I think the Bible teaches is in fact what the Bible teaches, and you agree, then you will change your view because you believe that that is the Word of God.

Many people are troubled by the fact that the Bible has been interpreted in so many ways and, as a result, have fallen into a view of relativism, which completely destroys the real significance of Scripture. It may be extremely difficult for us to find the proper interpretation, and we may be discouraged by all the disagreement about it, but part of the reason we fight so much among ourselves on matters of biblical interpretation is that we all agree that it’s crucial to understand the Word of God correctly.

»In an earlier book I wrote titled Psychology of Atheism (later released under the title If There Is a God, Why Are There Atheists?), I had a whole chapter about why scholars disagree. Not only do we find Christians disagreeing about what the Bible teaches, but some of the greatest minds in history disagree on some very significant points. I would say that there are three primary reasons great minds disagree on fundamental issues.

One is that we are prone to logical errors. We are given the capacity [p. 67] to reason, but we are not perfect in our reasoning powers. We will make illegitimate inferences. We will commit errors that violate the laws of logic. I remember when I studied the introduction to logic in college and was given examples of fallacies. The examples printed in our textbooks were not drawn from tabloid newspapers or comics but from the writings of some of the most brilliant people in history: Plato, John Stuart Mill, and David Hume. These men are universally recognized as some of the most brilliant people who ever walked the face of the earth. They made glaring logical errors that served as illustrations of how not to reason in an “Introduction to Logic” textbook. Mental errors are the first reason.

The second reason is empirical errors. Every one of us is limited in our perspective and field of experience. Not one of us has been able to survey all of the data. Sometimes our eyesight or our hearing fails us. We are limited in the senses we use to perceive reality around us. Limitations of sense perception add to making mistakes.

And the third great cause for error, whether it’s in understanding the Bible or in understanding science, is bias. We’re prejudiced. Sometimes we come to a problem or to a study biased against the data. We don’t want to believe what the data will tell us. When we become Christians, we are not cleansed of the ability to sin. We don’t always want to believe what the Bible teaches, and so we will make errors of interpretation as a result of our clouded thinking because of the hardness of our own hearts or because we don’t know the tools of biblical study. We haven’t learned the language sufficiently, or we have not been skilled or trained in legitimate inferences or the laws of immediate inferences, and so on.

The main reason Christians disagree on what the Bible teaches is that we are sinners. It’s a sin to misunderstand the Bible and to misinterpret the Bible because ultimately it’s a result of our being less than fully diligent in applying ourselves to seeking the truth of God’s Word. We have the assistance of the Holy Spirit, and we’re called to love God with all of our minds. The person who loves God with all of his mind is not casual in how he handles the Scriptures.

»That’s a problem that plagues all of us. There are some theoretical things we can say about it, but I’d rather spend time on the practical.

The Roman Catholic Church believes that one function of the church is to be the authorized interpreter of Scripture. They believe that not only do we have an infallible Bible but we also have an infallible interpretation of the Bible. That somewhat ameliorates the problem, although it doesn’t eliminate it altogether. You still have those of us who have to interpret the infallible interpretations of the Bible. Sooner or later it gets down to those of us who are not infallible to sort it out. We have this dilemma because there are hosts of differences in interpretations of what the popes say and of what the church councils say, just as there are hosts of different interpretations of what the Bible says.

Some people almost despair, saying that “if the theologians can’t agree on this, how am I, a simple Christian, going to be able to understand who’s telling me the truth?”

We find these same differences of opinion in medicine. One doctor says you need an operation, and the other doctor says you don’t. How will I find out which doctor is telling me the truth? I’m betting my life on which doctor I trust at this point. It’s troublesome to have experts differ on important matters, and these matters of biblical interpretation are far more important than whether or not I need my appendix out. What do you do when you have a case like that with variant opinions rendered by physicians? You go to a third physician. You try to investigate, try to look at their credentials to see who has the best training, who’s the most reliable doctor; then you listen to the case that the doctor presents for his position and judge which you are persuaded is more cogent. I’d say the same thing goes with differences of biblical interpretations.

The first thing I want to know is, Who’s giving the interpretation? Is he educated? I turn on the television and see all kinds of teaching going [p. 69] on from television preachers who, quite frankly, simply are not trained in technical theology or biblical studies. They don’t have the academic qualifications. I know that people without academic qualifications can have a sound interpretation of the Bible, but they’re not as likely to be as accurate as those who have spent years and years of careful research and disciplined training in order to deal with the difficult matters of biblical interpretation.

The Bible is an open book for everybody, and everybody has a fair shot of coming up with whatever they want to find in it. We’ve got to see the credentials of the teachers. Not only that, but we don’t want to rely on just one person’s opinion. That’s why when it comes to a biblical interpretation, I often counsel people to check as many sound sources as they can and then not just contemporary sources, but the great minds, the recognized minds of Christian history. It’s amazing to me the tremendous amount of agreement there is among Augustine, Aquinas, Anselm, Luther, Calvin, and Edwards—the recognized titans of church history. I always consult those because they’re the best. If you want to know something, go to the pros.

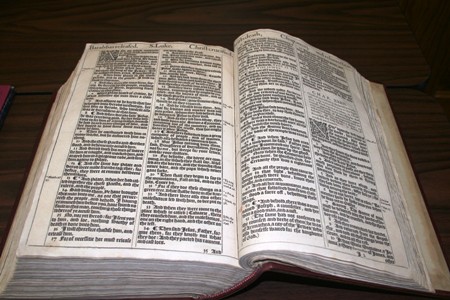

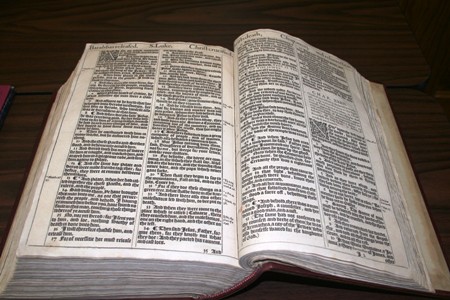

Even though we think of the Bible as being one book, it’s actually a collection of sixty-six books, and we realize that there was a historical process by which those particular books were gathered together and placed in one volume that we now know as the Bible. In fact, we call the Bible the canon of sacred Scripture. Canon is taken from the Greek word canon, which means “measuring rod.” That means it is the standard of truth by which all other truth is to be judged in the Christian life.

There have been many different theories set forth over the history of the church as to exactly how God’s hand was involved in this selection process. Skeptics have pointed out that over three thousand books were candidates for inclusion in the New Testament canon alone, and only a handful (twenty–some books) were selected. Doesn’t that raise some serious questions? Isn’t it possible that certain books that are in the Bible should not be there and others that were excluded by human evaluation and human judgment should have been included? We need to keep in mind, however, that of those not included in the last analysis, there were at the most three or four that were given serious consideration. So to speak in terms of two or three thousand being boiled down to twenty-seven or something like that is a distortion of historical reality.

Some people take the position that the church is a higher authority than the Bible because the only reason the Bible has any authority is [p. 62] that the church declared what books the Bible would contain. Most Protestants, however, take a different view of the matter and point out that when the decision was made as to what books were canonical, they used the Latin term recipemus, which means “we receive.” What the church said is that we receive these particular books as being canonical, as being apostolic in authority and in origin, and therefore we submit to their authority. It’s one thing to make something authoritative, and it’s another thing to recognize something that already is authoritative. Those human decisions did not make something that was not authoritative suddenly authoritative, but rather the church was bowing, acquiescing to that which they recognized to be sacred Scripture. We cannot avoid the reality that though God’s invisible hand of providence was certainly at work in the process, there was a historical sifting process and human judgments were made that could have been mistaken. But I don’t think this was the case.

»The church met in various historic councils, in which the representatives of the church examined the documents that were up for possible inclusion. I might mention that a few of those that were not to be included involved one of the early letters of Clement of Rome, who was the bishop of Rome around A.D. 95. One of the reasons Clement’s letter was not included in the Canon was that Clement, in his own writing, acknowledged the superiority of the apostles’ writings.

By what criteria did the church councils evaluate those candidates for admission into the church canon? One was apostolic origin; that is, if it could be shown that a book was written by an apostle of Jesus Christ, that book was accepted into the Canon. For example, we see that the Gospel of Matthew was written by one of the twelve disciples and a member of the apostolic body, so his book was accepted as canonical from the very beginning. It didn’t take until the final council at the end of the fourth century for Matthew to be included. It was there from day one.

You also have books like Mark. Mark was not an apostle, but Mark was the writer for Peter, and we know that Peter’s authority stood behind Mark, so Mark’s Gospel was accepted very early in the Christian church. Paul’s letters were accepted from the very beginning; even Peter’s letters call Paul’s letters “scripture.” Another criterion was a book’s acceptance in the early church community. Also required was conformity with that core of books about which there was never any doubt. The handful of books that were debated went against what was already clearly established as Scripture.

»This is one important point of dispute between historic Roman Catholic theology and classical Protestant theology. The Roman Catholic Church has gone on record, particularly at the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century, to declare that not only were the individual authors inspired in the writing of the individual books but that the church operated and functioned infallibly in the sifting and sorting process by which the canon of the New Testament, for example, was established.

To put it briefly, Rome believes that the New Testament is an infallible collection of infallible books. That’s one perspective. Modern critical scholarship, which rejects the infallibility of the individual volumes of Scripture and likewise the whole of Scripture, would say that the canon of Scripture is a fallible collection of fallible books.

The historic Protestant position shared by Lutherans, Methodists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and so on, has been that the canon of Scripture is a fallible collection of infallible books. This is the reasoning: At the time of the Reformation, one of the most important issues in the [p. 64] sixteenth century was the issue of authority. We’ve seen the central issue of justification by faith alone, which was captured by the slogan the Reformers used: sola fide, “by faith alone [we are justified].” Also there was the issue of authority, and the principle that emerged among Protestants was that of sola scriptura, which means that Scripture alone has the authority to bind our conscience. Scripture alone is infallible because God is infallible. The church receives the Scripture as God’s Word, and the church is not infallible. That is the view of all Protestant churches.

The church has a rich tradition, and we respect the church fathers and even our creed. However, we grant the possibility that they may err at various points; we don’t believe in the infallibility of the church. I will say that there are some Protestants who believe that there was a special work of divine providence and a special work of the Holy Spirit that protected the Canon and the sorting process from mistakes. I don’t hold that position myself. I think it’s possible that wrong books could have been selected, but I don’t believe for a minute that that’s the case. I think that the task the church faced and did was remarkably well done and that we have every book that should be in the New Testament.

When I discuss biblical concepts with my friends, I’m often met with the reply “That’s your interpretation.” How should I respond?

That is such a common response. You labor over a passage and do your homework, then present the passage, and somebody looks at you and says, “Well, that’s your interpretation.”

What do they really mean when they say that? That anything you say must be wrong, and since this is your interpretation, then it must be an incorrect one? I don’t think people are trying to insult us. The real issue here is whether or not there is a correct and incorrect interpretation of Scripture. When many people say, “That’s your interpretation,” what they really mean is, “I’ll interpret it my way, and you interpret it your way. Everybody has the right to interpret the Bible however they want [p. 70] to. Our forefathers died for the right of what we call private interpretation: that every Christian has the right to read the Bible for themselves and to interpret it for themselves.”

When interpretation became an issue in the sixteenth century at the Council of Trent, the Roman Catholic Church took a dim view of it. One of their canons at the fourth session said that nobody has the right to distort the Scriptures by applying private interpretations to them. Insofar as that statement is recorded at Trent, I agree with it with all of my heart because it’s exactly right. Though I have the right to read the Bible for myself and the responsibility to interpret it accurately, nobody ever has the right to interpret the Bible incorrectly.

I believe there is only one correct interpretation of the Bible. There may be a thousand different applications of one verse, but only one correct interpretation. My interpretation may not be right and yours may not be right, but if they’re different, they can’t both be right. That’s relativism taken to its ridiculous extreme. When someone says, “Well, that’s your interpretation,” I would respond, “Let’s try to get at the objective meaning of the text and beyond our own private prejudices.”

»It seems that every time a new translation of the Bible appears in the bookstores, there’s a certain degree of controversy that attends its appearance. People tend to prefer some tried–and–true translation. The first translation of the Bible from the original languages into the vernacular became such a controversial matter that those who dared to translate the Bible into German or English were, in many cases, executed.

For many years the authorized version in English was the King James Version. When a more up–to–date translation took place, such as the Revised Standard Version, there was a tremendous cry of protest against it. That protest goes on even today from those who prefer the King James edition.

There are basically two reasons we have this proliferation of new translations. One is that in the twentieth century we’ve experienced an explosion of knowledge and data about ancient lexicography, or word meaning. We’ve had so many more discoveries that shed light on the precise meaning of Hebrew and Greek words that our ability to translate the original documents accurately has been sharply increased. When that happens, it calls for a new translation. When you translate a document from one language to another, you run the risk of losing some of the precision that’s in the original. Whenever you have a better grasp of the original, you want to reflect that in the next edition of your translation.

Second, we’ve discovered many more texts of the Greek New Testament, and to be very frank, the Greek manuscripts from which the King James Version was translated were not the best Greek manuscripts. Since the King James was first introduced, we’ve had great progress in reconstructing the original manuscripts of the Bible, and that’s another reason for an update.

There’s still another reason, and that is that language changes and words that once meant one thing in a culture now mean another. Gay meant “happy” twenty years ago; that’s not what it means now. Cute meant “bow-legged” two hundred years ago; that’s not what it means now. Words do undergo an evolution, and that has to be reflected in new translations. There are also different types of translations. Some try to be very accurate, word for word, and others try to give more of a paraphrase. I see The Message as an attempt to simplify and paraphrase and speak in general terms. People find it a delightful help. I wouldn’t recommend it as the most strictly accurate version for careful technical study, but in simplifying the often arcane message of Scripture, I think it has done a tremendous service to the people of God.

»I think it does, obviously, in what the Bible says about itself. And what the Bible says about itself is very important to the modern debate about its authority in the life of the church and in the life of the individual believer.

One of the greatest debates in our age is this question of biblical authority. Even if the Bible didn’t claim authority over us, the church might still recognize it as a primary source and say, “This is the original information that we have of the teachings of Jesus.” Jesus obviously has a claim of authority over every believer inasmuch as he is the Lord of the church and the Lord of every believer. And we might still attribute that kind of authority to the Scriptures.

But the authority of the Bible is not proven by its claim. It is very significant, however, that it makes the claim to be the Word of God. Now anything that is the Word of God, it would seem to me, carries with it automatically nothing less than the authority of God. The great debate in our day is whether or not the Bible is inspired or infallible or inerrant. These are the kinds of controversies about which denominations are fighting in the Christian world today. And behind all of that debate, really, is the question of the extent of the Bible’s authority.

To illustrate it, let me share a brief anecdote about a friend of mine who said he had abandoned any confidence of the Bible’s inspiration or of its infallibility. He said, “But I’ve still maintained my belief in Christ as my Lord.” I said to him, point-blank, “How does Jesus exercise his lordship over you?” And he said, “What do you mean?” I replied, “A lord is somebody who has the authority to bind your conscience, to give you marching orders, to say, ‘You must,’ ‘You ought,’ ‘This is required of you.’ How does Jesus become your Lord? How does he speak to you? Does he speak audibly, directly, or what?” Finally he realized that the only message that we ever have from Jesus comes to us through the medium of the Scripture.

So the authority that the Bible has over me is the authority that [p. 73] Christ has over me, because when he sent out his apostles he said to them, “Those who receive you, receive me.” And it’s the authority of Christ given to his apostles that we find in Scripture. And if it comes from Christ and hence from God, then, of course, all of the authority of God stands behind it and over me.

»We divide the Bible into two sections, what we call the Old Testament and the New Testament, or the book of the old covenant and the book of the new covenant. In one very real sense, historically, the writings of Scripture are part of the written documents of a covenant agreement between God and certain people. In the Old Testament it is a covenant agreement between God and the Jewish people. And the new covenant is called the covenant of Christ for his people.

Insofar as the nonbeliever has not entered into a covenant relationship with God, there is a sense in which he becomes an alien to the commonwealth of Israel or to the new covenant community of Christ and therefore is not formally bound by oath to the stipulations of that covenant agreement, part of which are the writings of sacred Scripture. However, we also have to recognize that every human being is created in the image of God. By virtue of a person’s humanness, he or she is inextricably bound into a covenant relationship with the Creator. So if I choose not to believe in God or not to serve God or not to be involved in religion in any way, that does not destroy God or his existence, or change the fact that I have been created by God and am accountable to God and am required by God to obey him and to worship him and to heed his voice. So coming at it from that angle, we would say that the unbeliever, in spite of his unbelief, is still responsible to heed whatever God says. And if the Scriptures are the Word of God, then they carry the authority of God. If you were to ask, “Does God have authority over the unbeliever?” I would say, “Of course he does.” And anything that God says is authoritative to all people.

»The Scriptures are not a single book but a collection of books made up of sixty-six volumes in the particular library that we call the Bible. The New Testament covers a period of time in human history of about thirty-five years, and all but five of those years for the most part are covered in the first couple of chapters. So the bulk of the New Testament covers about a five–year period in human history. It is the most important period in human history of God’s dealing with the human race because it covers the earthly ministry of Jesus and the expansion of the early church.

The Old Testament, beginning around Genesis 11 and throughout the rest of the Old Testament, covers a period of about two thousand years of redemptive history. That is a wealth of information of how God has acted on behalf of his people and for the redemption of this world.

I don’t think we can say that one is more pertinent than the other. There is a widespread feeling that a Christian is only to be concerned with the New Testament, that the Old Testament is antiquated, no longer truly relevant. In fact, there is more and more the feeling that there are two different Gods. There is the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New Testament. The God of the Old Testament is a God of anger, wrath, justice, and holiness. The New Testament God focuses on love, mercy, and grace. That, of course, is a radical distortion. There is a continuity between the two Testaments. We can distinguish them, but we dare not separate them. The same God is revealed to us both in the Old Testament and in the New Testament. Saint Augustine said, “The Old is in the New revealed; the New is in the Old concealed.”

The Old Testament is preparation for the coming of the Messiah and the revelation that we receive in the New Testament. It’s like asking, “Is the foundation of a house important? Is it pertinent to the house?” It’s essential to the house. The structure stands upon that foundation, and that’s what the Old Testament does for our faith. There are many elements of Old Testament history that are not to be applied directly to the Christian life today, such as the sacrificial system, but even the dimension of the sacrificing of bulls and goats and the like that we find in the Old Testament reveals something that points to the coming of Christ and enriches our understanding of what was accomplished by Christ. About three-fourths of the information in the New Testament is either a quotation of, an allusion to, or a fulfillment of something that was already found in the Old Testament.

»One of the great weaknesses of today’s church is a tendency to denigrate and neglect the Old Testament. It’s a much more sizable piece of literature than the New Testament, and it covers an enormous period of history, the history of redemption from the creation of the world until the appearance of the Messiah. All of that is a revelation of God’s activity on this planet, and I believe it was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church for the church’s instruction and for the church’s edification.

I also think that one of the great problems in today’s church is an abysmal ignorance of God the Father. We relate to Jesus. He’s our Redeemer. He’s God in the flesh, so we have a way in which we can understand Jesus. It is more difficult when we look at God the Father and also the Holy Spirit. The history of the Old Testament certainly calls forth something of the Messiah who is to come, but it is constantly revealing the character of God the Father, the one who sends Jesus into this world, the one whom Jesus calls Father, the one from whom Jesus says he has [p. 76] been sent, that person to whom we are being reconciled and redeemed. So how can we possibly justify neglecting such an enormous body of literature that communicates to us the character, nature, and will of our Creator and the one who has sent our Redeemer to this planet?

Saint Augustine is the one who said that the New Testament is concealed in the Old Testament and the Old Testament is revealed by the New Testament. In fact, about three-fourths of the material of the New Testament is either a quotation from or allusion to what went before it. I don’t think we can really understand the New Testament until we have made a very serious study of the Old Testament.

Obviously there are things in the Old Testament that do not apply to the Christian in our day. For example, we are not to continue the ceremonies that were required of the Jewish people; those ceremonies were “types” that anticipated the once–for–all fulfillment of them in the work of Christ. So for us to offer animals as sacrifices would be an insult to the completion of Jesus’ work on the cross. That doesn’t mean that since that part of the Old Testament is fulfilled we are to neglect it altogether. The Old Testament is a treasure-house of knowledge for the Christian who will seek to investigate it.

»There is no single view of evolution out there. We make one distinction, for example, between macroevolution and microevolution. Macroevolution claims that all of life evolved fortuitously from a single cell—one little pulsating cell of life made up of amino acids and RNA and DNA and all of that, and then through chance, explosions, or whatever, there were mutations. First, a lower, simplistic form of life came about, and then from that came more complex things, and we all emerged, as it were, from the slime, through oozing, into our present humanity. That’s the radical view of evolution that sees life occurring as sort of a cosmic accident.

This view of evolution—the one I hear discussed publicly so often in [p. 77] the secular world—is unmitigated nonsense and will be totally rejected by the secular scientific community within the next generation. My objections to it are not so much theological as they are rational and logical. I mean, the doctrine of macroevolution is one of the most unsubstantiated myths that I’ve ever seen perpetuated in an academic environment.

But there are other varieties much less radical that simply indicate that there is a change, a progression involving different directions among various species that we can even track historically. The kind of evolution of the latter sort is of no consequence with respect to biblical Christianity. The big issue is with the former view, and this is the basic question: Is man in his origin the product of a purposive act of divine intelligence, or is man a cosmic accident? In other words, am I a creature of dignity or a creature of cosmic insignificance? That’s a pretty heavy issue because if I just sort of popped into being or emerged from the slime and I’m destined for annihilation, I can only fantasize that somehow in between those two poles of origin and destiny I have meaning and significance and dignity. But that’s wishful thinking of the worst sort. Obviously if I come from nothing and go to nothing, I am nothing under any objective analysis.

A Christian cannot believe that he is a cosmic accident and at the same time believe in the sovereign God and the creator God. To be a Christian is to affirm not only Christ the Redeemer but God the Creator. And we have to affirm both. Let me say, too, before we drop this question, that some of the biggest objections I have toward this more radical view of evolution are not the theological problems, as serious as they are, but rational problems. I think that it is not only bad theology, it’s bad science.

All Christians, Jews, and Muslims historically have made it a central article of affirmation that this world and all the people in it are the result of a divine act of creation. As far as Christianity is concerned, if there’s no creation, then there’s nothing to redeem.

»What does the Bible tell us about the age of the earth? I remember once opening a Bible that was on the pulpit of a church. I opened it to the first page because I was preaching from the first chapter of Genesis, and it said, “The Book of Genesis,” and then underneath “The Book of Genesis” in black boldfaced numbers was this: “4004 B.C.” Right there on the first page of Scripture. I laughed.

I thought it was funny because there was a man by the name of Archbishop Usher a couple hundred years ago who, in reading the genealogies in the Bible, calculated an average lifespan of all those mentioned in the genealogy and came up with a highly speculative figure of 4004 as the date of Creation and tried to make a case that the Bible actually called for the creation of the world in 4004 B.C. What disturbed me was to see that number actually printed on the page of Holy Scripture. Now if somebody who doesn’t know the origin of that kind of speculation picks up the Bible and reads on the page of Scripture “4004 B.C.” and their mother or their Sunday school teacher tells them that the world was created 4,000 years before Christ, but the scientific evidence indicates that the universe is billions of years old, then they get all upset and think that somebody is attacking the Bible. When the fact of the matter is, the Bible doesn’t give the slightest indication of when Creation occurred. So we really shouldn’t be concerned about it.

»I have lots of frustrations about teaching. But I would say my greatest frustration is that there is a tremendous anti-intellectual spirit present in contemporary Christendom. It’s extremely hard to educate people who are opposed to using their minds. How else can we get educated?

There are reasons for this attitude. Evangelical Christians, for example, have seen a wholesale attack upon the sacred things that they believe [p. 79] and live by—the Bible and all the rest—by colleges and universities, by professors and theologians. They’ve come to distrust serious education. They want to keep their faith simple lest it be open to some kind of criticism or attack. I hear it constantly. “You have to take it on faith,” as if seeking to understand something were evil. And how many times have you heard people say that they want to have childlike thinking?

What the Bible says, however, is that we are to be “babes in evil,” that we are to be like little children in terms of being not sophisticated in our capacity for sin. But in understanding we are to be full-grown and mature. We are to put away childish things. I am very frustrated with the resistance I encounter in the Christian community against in-depth study of the things of God.

My second great frustration is that so many Christians, in order to truly learn the things of God, first have to unlearn what they’ve already learned. It’s not by accident that the greatest threat to the integrity of Old Testament Israel and to the safety of the nation was not the opposing nations like the Philistines and the Babylonians but the enemy within—the false prophet. And the false prophet seduced the people away from the truth of God. Now that happens today, and it happens on both sides of the camp—the liberals and conservatives. And so what happens is people are educated with teaching that is not sound, and that’s frustrating.