Some forms of contemporary Judaism do not include a belief in life after death. We know that in Jesus’ day there was a great debate over that point between two parties of the contemporary Jewish nation, the Pharisees and the Sadducees. The Pharisees believed in life after death; the Sadducees did not. You would think that those who were leaders in the household of Israel would be agreed on a point like that if it were spelled out with obvious clarity in the Old Testament.

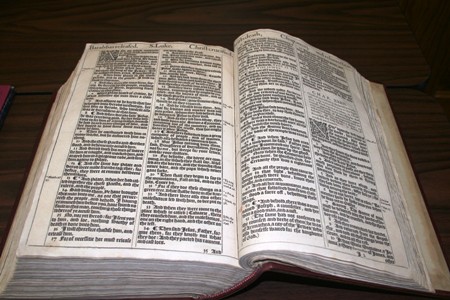

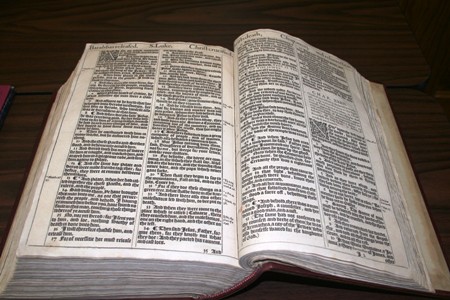

Of course, one of the debates between those two parties was what constituted the Old Testament. Was it just the first five books of Moses, or did it include all of what today’s Christian would consider to be the Old Testament—the Prophets and the Wisdom Literature? The concept of life after death in the Old Testament (indicated often by references to Sheol) is somewhat vague and shadowy; death is depicted as a place beyond the grave where both good and bad people go. The clarity with which the New Testament proclaims life after death is not found in the same dimension in the Old Testament. I think it’s there, and if you study the Major Prophets, particularly Isaiah, you will see that the teaching of life after death is clearly set forth in the Old Testament. However, I’m looking at the Old Testament with the benefit of the information coming to me through the New Testament.

Certainly there were lots of folks who read the same Old Testament material and didn’t see references to afterlife so clearly. During Job’s struggle with earthly trials, he asked, “If a man dies, will he live again?” We see later that Job says in a note of triumph and as an expression of confidence and faith, “I know that my Redeemer liveth, and I will see him standing on that day.” Christians have looked back at that and said, “Well, if Job is that confident of a redeemer who will set him free in some distant future, then obviously this is an expression from great antiquity of confidence in life after death.” But Job’s word that is translated “redeemer” actually means “vindicator.” Job is simply saying that he is confident he will be vindicated. Now, whether or not that included [p. 223] in Job’s mind an ultimate vindication in heaven is again subject to some debate.

David’s confidence, however, of future reunion with his child who had died is a clear indication of his confidence in an afterlife. It was not unknown among the Old Testament saints that there would be a future life. It simply is not as clear as it is in the New Testament.

»On the one hand, Old Testament teaching on the afterlife is somewhat vague. We hear the use of the word Sheol, which seems to incorporate both the negative and positive elements of life after death. We certainly find more clear references to heaven in the New Testament, but many passages in the Old Testament, including some of David’s psalms and parts of the book of Isaiah, call attention to the reality of heaven.

Did faithful people of that time go to heaven or to a waiting place? The Roman Catholic Church has the doctrine of limbo we’ve heard about, mainly with respect to babies. The broader concept included the “limbo of the fathers”—a place where people in the Old Testament who died in faith had to go and wait until Christ accomplished his work of redemption on the cross.

There’s a link between that view, which is held in many circles, and the very cryptic reference in Peter’s writings about what happened to Jesus after he died—that he went and preached to the spirits in prison (1 Pet. 3:19). Some people interpret “the spirits in prison” to mean the Old Testament saints who were being held captive until the work of Christ’s redemption was completed. He released them to enter into paradise with him. Jesus was the “firstborn from the dead”; he went first to the place of the dead and led out the captives, bringing these people into their state of future glory.

I’m inclined to think that Old Testament saints had immediate access [p. 224] to paradise because heaven itself is called “the bosom of Abraham” in the New Testament. That’s not a likely descriptive term for heaven if it’s some place from which Abraham was absent.

Also, based theologically on our doctrine of redemption, I think that Paul teaches in Romans 3 and 4 that salvation occurs exactly the same way in the Old Testament as it does in the New Testament—through faith. The only difference is that Old Testament faith was in a future promise that had not yet been fulfilled. The people believed, and when they believed, they were justified and counted worthy to be in the presence of God. In the New Testament we look backward to a work that is accomplished. We know that the Old Testament sacrifices had no efficacy in and of themselves; they represented the future work of Jesus, who ultimately paid for all sin. Since salvation comes to us on the basis of the merits of Christ, I see nothing that would prevent God from opening the gates of heaven prior to the Cross, even though he does it in light of the Cross.

»When I was in seminary, I studied under an extremely learned professor who I was convinced at the time knew the answer to every possible theological question. I remember I was so in awe of him that I asked him one day with stars in my eyes, “What’s heaven like?” I asked him as if he had been there and could give me a firsthand report! Of course, he steered me immediately to the last two chapters of the New Testament, Revelation 21 and 22, in which we get an extensive visual image of what heaven is like. Some dismiss it as being pure symbolism, but we must remember that the symbols in the New Testament point beyond themselves to a deeper and better reality than they themselves describe. It’s here that we read of the streets of gold and of the great treasuries of jewels that adorn the New Jerusalem that comes down from heaven.

In the description of the New Jerusalem, we hear that there’s no sun and no moon, no stars, because the light that radiates from the presence of God and from his Anointed One is sufficient to illumine the whole place by the refulgence of their glory. We are told that there’s no death, there’s no pain, and God wipes away the tears of his people.

I remember as a child having that tender experience (not often accessible to adults) in which I would scrape my knee, or something would go wrong, and I would cry and come into the house, and my mother would stoop over and dry the tears from my eyes. I received great consolation from that. But of course, when my mother dried my tears, there was always the opportunity the next day for me to cry again. But in heaven when God wipes away the tears from people’s eyes, that’s the end of tears—there are no more tears after that. And so heaven is described as a place of utter felicity that is filled with the radiant majesty and glory of God, where God’s people have become sanctified, where justice has been brought to bear, and where his people have been vindicated. There’s no more death, no more disease, no more sorrow, no more sickness, no more hatred, and no more evil. And then there is an experience of healing in that place. And that’s just a glimpse, but it’s enough to get us started.

I’m not sure heaven is described as little as we may think. We sometimes get the feeling that there’s not much in there about heaven, but if we examine the Scripture text, we’ll find a wealth of material that speaks on that subject— particularly in the New Testament teachings of Jesus, as well as from the book of Revelation. Maybe there’s not as much in there about heaven as we would like to find. Since it is the ultimate destination of the Christian, you’d think there would be a bit more spelled out about the nature of heaven.

As it is depicted in the Scriptures, heaven represents a radical change from what we experience in this world. In other words, there is a tremendous amount of discontinuity between the life I live on this earth and what awaits me in heaven. Anytime you have discontinuity between experiences, the only way you can speak meaningfully about them is through some sort of analogy. We’ve never experienced this different life that is called heaven. It’s very difficult to discuss something we’ve never experienced. That’s why I think the Bible uses analogies. The writers will say heaven is like this or that because they are trying to find some meaningful reference point in this present world that will speak to us about that which “eye has not seen, nor ear has heard, nor has entered in the heart of man.” It is that which transcends our ability to anticipate.

Sometimes we learn about something by finding out what it’s not. For example, in Revelation the Bible tells us that in heaven there is no crying, there’s no pain, no death, no sorrow, no darkness. On the one hand, I can’t conceive of what life would be without any of those things; yet at the same time I have some idea of the difference between light and darkness, peace and warfare, joy and sorrow, and so on. I think the main reason we’re not given more information is that we are so limited in our ability to anticipate that which is so much greater than we can even imagine in this world.

»This may come as a surprise to many people, but I would answer that question with an emphatic yes. There are degrees of reward that are given in heaven. I’m surprised that this answer surprises so many people. I think there’s a reason Christians are shocked when I say there are various levels of heaven as well as gradations of severity of punishment in hell.

We owe much of this confusion to the Protestant emphasis on the doctrine of justification by faith alone. We hammer away at that doctrine, teaching emphatically that a person does not get to heaven through [p. 227] his good works. Our good works give us no merit whatsoever, and the only way we can possibly enter heaven is by faith in Christ, whose merits are imputed to us. We emphasize this doctrine to the extent that people conclude good works are insignificant and have no bearing at all upon the Christian’s future life.

The way historic Protestantism has spelled it out is that the only way we get into heaven is through the work of Christ, but we are promised rewards in heaven according to our works. Saint Augustine said that it’s only by the grace of God that we ever do anything even approximating a good work, and none of our works are good enough to demand that God reward them. The fact that God has decided to grant rewards on the basis of obedience or disobedience is what Augustine called God’s crowning his own works within us. If a person has been faithful in many things through many years, then he will be acknowledged by his Master, who will say to him, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” The one who squeaks in at the last moment has precious little good works for which he can expect reward.

I think the gap between tier one and tier ten in heaven is infinitesimal compared to the gap in getting there or not getting there at all. Somebody put it this way: Everybody’s cup in heaven is full, but not everybody in heaven has the same size cup. Again, it may be surprising to people, but I’d say there are at least twenty-five occasions where the New Testament clearly teaches that we will be granted rewards according to our works. Jesus frequently holds out the reward motif as the carrot in front of the horse—“great will be your reward in heaven” if you do this or that. We are called to work, to store up treasures for ourselves in heaven, even as the wicked, as Paul tells us in Romans, “treasure up wrath against the day of wrath.”

»No specific biblical reference declares explicitly that we will recognize each other. But the implicit teaching of Scripture is so overwhelming that I don’t think there’s really any doubt that we will be able to recognize each other in heaven. There is an element of discontinuity between this life and the life to come: We’re going to be changed in the twinkling of an eye; we’ll have a new body, and the old will pass away. Nevertheless, the Christian view of life after death is not like the Eastern view of annihilation, in which we lose our personal identities in some kind of a sea of forgetfulness. Even though there is this element of discontinuity, replacing the old with the new, there’s a strong element of continuity in that the individual person will continue to live on into eternity.

Part of what it means to be an individual person is to be involved in personal relationships. In fact, one of the articles of the Apostles’ Creed is that we say we believe in the communion of the saints. That affirmation does not apply only to the fellowship that we enjoy with each other now, but it indicates a communion that all people who are in Christ have with one another. Even now, in this world, I mystically enter into communion with Martin Luther and John Calvin and Jonathan Edwards, who are part of the whole company of saints. There’s no reason to expect that this communion will cease.

When we enter into a better level of communion with Christ and with those who are in Christ, we would think that communion would naturally intensify rather than diminish.

Although you have to be careful about how much you draw out of a parable, Jesus’ parable about the rich man and Lazarus does give us an inside look at the afterlife. He talks about a rich man who had everything going for him in this world and a poor man who was a beggar at the rich man’s gates. The rich man ignored the pleas of the poor man. Both of them died, and the poor man, Lazarus, was carried to the bosom of Abraham, whereas the rich man was in the outer darkness. But even there this one who was presumably in hell was able to see across the unbridgeable chasm to the bosom of Abraham and see the state of felicity this beggar was now enjoying. He pleaded with Abraham, crying across the gulf, to have mercy and to let him have the power to go back to earth or to send a message back to warn his own brothers lest [p. 229] they fell into the judgment he had fallen into. Of course, Jesus says it’s too late at that point. At least in the parable there is recognition of the persons involved and also recognition of where people are and where they aren’t.

»I can’t answer that question for sure, but I don’t want you to think for a minute that it’s a frivolous question. People do get very attached to their pets, particularly if the pet has been with them for a long time. In our present culture more and more pet cemeteries are appearing, and we see people going to great expense and ceremony—gravestones and all—to dispose of the bodies of their pets.

Within the Christian church there are different schools of thought on this issue. Some people believe that animals simply disintegrate; they pass into nothingness and are annihilated, which is based on the premise that animals don’t have souls that can survive the grave. However, nowhere does Scripture explicitly state that animals do not have souls.

The Bible tells us that we have the image of God in a way that animals do not. Now is the “image of God” what differentiates between a soul and a nonsoul? Those who take a Greek view of the soul—that it is this substance that continues indestructibly forever—may want to restrict that to human beings. But again, there’s nothing in Scripture I know of that would preclude the possibility of animals’ continued existence.

The Bible does give us some reason to hope that departed animals will be restored. We read in the Bible that redemption is a cosmic matter. The whole creation is destined to be redeemed through the work of Christ (Rom. 8:21), and we see the images of what heaven will be like; beautiful passages of Scripture tell us about the lion and the lamb and other animals being at peace with one another. Whenever heaven is described, though it may be in highly imaginative language, it is a place where animals seem to be present. Whether these are animals newly created for the new heavens and the new earth, or they are the redeemed souls of our pets that have perished, we can’t know for sure.

All of this is sheer speculation, but I would like to think that we will see our beloved pets again someday as they participate in the benefits of the redemption that Christ has achieved for the human race.

I think it is possible for a person who has committed suicide to go to heaven. I say that for several reasons. Psychiatrists have studied people who have made serious attempts to take their own lives but failed in the process. When interviewed afterwards, the vast majority of these people (90 percent, according to the psychiatrists) said that they would not have attempted suicide had they waited twenty-four hours. So often the act of suicide is a surrender to an overwhelming but momentary attack of acute depression. We really don’t know the last thoughts that go through a person’s mind before he or she dies. Suppose a man decides to end his life and he jumps off a thirty–story building, and at the sixteenth story he’s thinking, This is a mistake; I shouldn’t do this. Obviously, there’s room in the grace of God for that man’s final repentance from that sin.

Even though the Scriptures are very clear that we are not to take our own lives, I know of nothing in Scripture that identifies suicide as the unforgivable sin. Now, if a person is ending his or her life in the full possession of their faculties, this act may represent a final and absolute act of unbelief, a surrender to despair and hopelessness rather than a confidence in the living God. However, I don’t think we can assume that this is the mental state of everyone who actually commits suicide.

Some people who attempt suicide are not in a sober state of thinking and not culpable for their behavior at the last moment. Since the Bible is relatively silent about that, I don’t like to jump to conclusions. I would prefer to rest our hope for such cases in the grace and the kindness of God.

»Throughout its history, the church has struggled with the concept of what is called the “intermediate state”—our position between the time we die and the time Christ consummates his kingdom and fulfills the promises that we confess in the Apostles’ Creed. We believe in the resurrection of the body. We believe there will be a time when God reunites our soul and our body, and that we will have a glorified body even as Christ came out of the tomb as the “firstborn from the dead.” In the meantime, what happens?

The most common view has been that, at death, the soul immediately goes to be with God and there is a continuity of personal existence. There is no interruption of life at the end of this life, but we continue to be alive in our personal souls upon death.

There are those who have been influenced by a cultic view called psychopannychia, more famously known as soul sleep. The idea is that at death the soul goes into a state of suspended animation. It remains in slumber, in an unconscious state, until it is awakened at the time of the great resurrection. The soul is still alive, but it is unconscious, so that there is no consciousness of the passing of time. I think this conclusion is drawn improperly from the euphemistic way in which the New Testament speaks about people in death being asleep. The common Jewish expression that they are “asleep” means they are enjoying the reposed, peaceful tranquility of those who have passed beyond the struggles of this world and into the presence of God.

But the overall teaching of Scripture, even in the Old Testament, where the bosom of Abraham was seen as the place of the afterlife, there is this persistent notion of continuity. Paul put it this way: To live in this world is good; the greatest thing that can ever happen is to be participating in the final resurrection. But the intermediate state is even better. Paul said that he was caught between two things. On the one hand, his desire was to depart and be with Christ, which is far better, and on the other hand, he had a desire to remain alive and continue his ministry on this earth. But the apostle’s judgment that the passing beyond the veil of death to that intermediate state is far better than this one gives us a clue, along with a host of other passages. Jesus said to the thief on the cross, “I say to you, today you shall be with me in paradise.” The image of Dives and Lazarus in the New Testament (Luke 16:19-31) indicates to me that there is a continuity of life and of consciousness in that intermediate state.

»In my own theological tradition, we believe that those children who die in infancy are numbered among the redeemed. That is to say, we hope and have a certain level of confidence that God will be particularly gracious toward those who have never had the opportunity to be exposed to the gospel, such as infants or children who are too disabled to hear and understand.

The New Testament does not teach us this explicitly. It does tell us a lot about the character of God—about his mercy and his grace—and gives us every reason to have that kind of confidence in his dealings with children. Some will make a distinction between infants in general and those who are children of believers, the reason being that when God made a covenant with Abraham, he made it not only with Abraham, but with Abraham’s descendants. In fact, as soon as God entered into that relationship with Abraham, he brought Isaac into it—when Isaac was still an infant and didn’t have an understanding of what was going on. This is the reason, incidentally, that a large number of Christian bodies practice the baptism of infants; they believe that children of believers are to be incorporated into full membership in the church. We see this relationship within the family in biblical history.

We also see David’s situation in the Old Testament when his infant child dies. Yet David is given the confidence that he will see that child again in heaven. That story of David and his dying child gives a tremendous consolation to parents who have lost infants to death.

Now the point that we have to make is that infants who die are given a special dispensation of the grace of God; it is not by their innocence but by God’s grace that they are received into heaven. There are great controversies that hover over the doctrine of original sin. Lutherans disagree with Roman Catholics, who disagree in turn with Presbyterians, etc., on the scope and extent of what we call original sin. Original sin does not refer to the first sin that was committed, but rather to the result of that—the entrance of sin into the world so that all of us as human beings are born in a fallen state. We come into this world with a sin nature, and so the baby that dies, dies as a sinful child. And when that child is received into heaven, he is received by grace.

»You are asking a question that the Christian church has been seriously divided over throughout its history for several reasons. There’s little information in Scripture that speaks about it directly. The Roman Catholic Church has its traditional doctrine of limbo, and limbo is of two varieties. There is the limbo for Old Testament people who died before the coming of Christ, and then there’s limbo for infants. Here, limbo is defined as sort of a lesser corridor of hell. It’s not heaven, but the historic definition is that it’s where the fires of judgment do not reach. The unbaptized babies are assigned to that place, where they lose the blessings of heaven but don’t actually participate in the punishments of hell.

Protestant churches differ on what happens to babies that die. Some distinguish between those who are baptized and those who are not. In my denomination, we hold as an article of faith that the children of believers are given a special dispensation of grace and are taken to heaven, not because they are innocent, but because they are recipients of grace.

Are unborn children the same as babies? Again, the controversy there is whether or not these unborn fetuses are, in fact, considered by God to be human lives. Some take the position that an aborted baby is a real human person, and it would seem consistent to say that whatever you think happens to babies who die in infancy would then, therefore, apply to unborn children. My personal belief is that unborn babies who die through abortion are treated as human beings by God and that the same grace he dispenses to babies who die in infancy would apply to unborn children. That doesn’t depend on whether the abortion is intentional or unintentional. The term abortion is also a term we use to describe a miscarriage. My wife has had four miscarriages, and we fully hope and expect to see those unborn children in heaven with us. We assume that we have six children and not only two, and we’re looking forward to a reunion with the children that we’ve never been able to know personally.

»I don’t think it was an act of God. Just recently, incidentally, I wrote a chapter in a book on that whole question of the witch of Endor because it’s such a provocative and difficult piece of Scripture to deal with. This narrative tells us that after the death of Samuel, Saul disguised himself and sought out a medium. Such mediums were outlawed in Israel, and the practice of this kind of activity was a capital offense. Not only was it a capital offense under the Mosaic law, but Saul himself had enforced this and insisted that all necromancers leave the land. That’s why Saul disguised himself. He went to this witch, or medium, and asked her to conjure up Samuel. The text says that Samuel appeared and complained about being disturbed. The woman then realized that it was the king who had induced her to do this, and she was terrified.

When I look at that, I have to ask this question: What really happened there? Is the Bible speaking in phenomenological language, describing what appeared, or does the Bible intend to say that the medium was in fact able to bring Samuel back from the dead? Was it the clever trick of a magician? Was it a natural ability, one that some people may have today? Is it possible today to contact the dead, or is it a counterfeit activity of Satan himself? I’m not altogether sure which of these, if any, explain the situation.

Let me say what we know for sure. If we can contact the dead today and conjure them up as you say, we’re certainly not allowed to. There’s no question about that. This is a radical offense to God. We’re simply not permitted to be involved in séances, in spiritualism, or in the use of mediums. That is anathema to God, and in fact, people who do that are included in the final chapter of the New Testament as those who are excluded from the kingdom of God. The warnings are severe and weighty about being involved in these kinds of activities.

But—is it possible? I don’t think so. I don’t think we can call forth the spirits of the dead. I believe all mediums resort to trickery to perform these feats. In the late nineteenth century, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle got enamored with the possibility, and the great Harry Houdini offered a large sum of money to any medium who could make any phenomenon occur that he couldn’t duplicate with his own art of illusion. No one ever collected the money from Houdini. The best “ghost busters” are magicians themselves. It takes a thief to know a thief. I’m persuaded that the people who are practicing this are hoaxers.

»I’m not sure I can explain the so-called Kübler-Ross phenomenon. There’s been a significant amount of research on this. I’ve heard reports saying that as many as 50 percent of those who have suffered clinical death and have been resuscitated through CPR or forms of medication [p. 236] report some kind of a strange experience that may be called an out–of–body experience. They report the sensation of looking down from the ceiling as their soul is leaving the body and seeing their own body lying in the bed and the doctor pronouncing them dead or a nurse not finding a pulse. Then they talk about going through this tunnel and seeing this marvelous light. The vast majority of those who have been researched have a very positive recollection, although there are some who don’t see lovely lights at the end of the tunnel but very ghastly and horrendous things that gave them pause about what might be beyond the veil.

I don’t know how to answer these questions. There are various possible answers. One could be that a person who is near death can have a short circuit in the electrical nervous system of their brain and can get their time sequences all messed up. They could be recalling a dream that was very vivid and intense that makes them feel as if they really lived it. All of us have some dreams that are qualitatively different from others, that become so intense that you feel as if it had actually happened. It could be the result of medication or the lack of oxygen to the brain.

To deal sufficiently with those possible explanations would require a competent physician who can talk about whether it’s possible for such short circuits to take place and whether it could be explained in natural terms. I haven’t ruled out the experience.

The other possible explanation is that people do, in fact, have a glimpse of something that’s about to take place in transition from death to wherever we go after death. We as Christians do believe that we have a continuity of personal existence and that the cessation of physical life is not the end of actual life. Whether we’re good or bad, whether we’re redeemed or unredeemed, we’re going to continue in a living state though not biologically alive. It shouldn’t shock the Christian when people undergoing clinical death and being revived come back with certain recollections. I’ve tried to keep an open mind, and I hope that this interesting phenomenon will get the benefit of further research, analysis, and evaluation. Too many of these experiences have been reported for us to simply dismiss them as imaginary or hoaxes.

»Of course, the first thing I want to know is, What do I have to do to see Jesus? I want to see the Lord. In the past I’ve asked friends and family members, “Suppose that after you got the chance to see Jesus in heaven he said, ‘OK, you can see any three people who are here and spend time one–on–one with those people’—who would you want to see?” The first person I would want to see would be my father. This is one of the great consolations of the Christian faith—we have the promise of reunion with those whom we love who have gone ahead of us. After seeing my father, I’d love to meet the psalmist David. I’d love to meet Jeremiah. And the list goes on.

One of the first questions I am going to ask is, “Who wrote the book of Hebrews?” I’m dying to find that out! Another question: “Where did evil come from?” because I haven’t been able to figure that one out. And, of course, I would have to know, “Are there any golf courses up here?”

I’d like to study art for the first ten thousand years, music for the next ten thousand years, and literature for the next ten thousand years and just continue to soak in everything that God has made and everything he has ordained. I’d love to sit there and learn theology with the full assurance that I am never being deceived or that I’m not making any errors and that I’m no longer looking through a glass darkly, but now I am in the presence of Truth itself, in all of its purity. But I suspect that those things that I think about doing will have to wait for the sheer joy of being in the presence of God and enjoying the beatific vision—of seeing Christ face–to–face. I don’t know if that would ever wear off. I’d be satisfied to just do that, I think, for eternity.

»That’s one of the most emotionally laden questions that a Christian can ever be asked. Nothing is more terrifying or more awful to contemplate [p. 238] than that any human being would go to hell. On the surface, when we ask a question like that, what’s lurking there is, “How could God ever possibly send some person to hell who never even had the opportunity to hear of the Savior? It just doesn’t seem right.”

I would say the most important section of Scripture to study with respect to that question is the first chapter of Paul’s letter to the Romans. The point of the book of Romans is to declare the Good News—the marvelous story of redemption that God has provided for humanity in Christ, the riches and the glory of God’s grace, the extent to which God has gone to redeem us. But when Paul introduces the gospel, he begins in the first chapter by declaring that the wrath of God is revealed from heaven and this manifestation of God’s anger is directed against a human race that has become ungodly and unrighteous. So the reason for God’s anger is anger against evil. God’s not angry with innocent people; he’s angry with guilty people. The specific point for which they are charged with evil is in the rejection of God’s self-disclosure.

Paul labors the point that from the very first day of creation and through the creation, God has plainly manifested his eternal power and being and character to every human being on this planet. In other words, every human being knows that there is a God and that he is accountable to God. Yet every human being disobeys God. Why does Paul start his exposition of the gospel at that point? What he’s trying to do, and what he develops in the book of Romans, is this: Christ is sent into a world that is already on the way to hell. Christ is sent into the world that is lost, that is guilty of rejecting the Father whom they do know.

Now, let’s go back to your original question, “Does God send people to hell who have never heard of Jesus?” God never punishes people for rejecting Jesus if they’ve never heard of Jesus. When I say that, people breathe a sigh of relief and say, “Then we’d better not tell anybody about Jesus because somebody might reject him. Then they’re really in deep trouble.” But again, there are other reasons to go to hell. To reject God the Father is a very serious thing. And no one will be able to say on the [p. 239] last day, “I didn’t know that you existed,” because God has revealed himself plainly. Now the Bible makes it clear that people desperately need Christ. God may grant his mercy unilaterally at some point, but I don’t have any reason to have much hope in that. I think we have to pay serious attention to the passionate command of Christ to go to the whole world, to every living creature, and tell them of Jesus.

»I was once asked that question by a student who put it to me this way, “Do you believe that hell is a literal lake of fire, where people are burning and in torment? Do you think there’s weeping and gnashing of teeth, darkness, and a place where the worm never dies?” He asked if I believed hell was literally like that, and I said no, I didn’t. He breathed a heavy sigh of relief. Then I said that I thought a person who is in hell would do everything in his power to be in a lake of fire rather than to be where he is. I really have no graphic picture of hell in my mind, but I can’t think of any concept more terrifying to the human consciousness than that concept. I know that it’s a very unpopular concept and that even Christians shrink in horror at the very idea of a place called hell.

I’ve always wondered about two phenomena that we find in the New Testament. One, that Jesus speaks more of hell than he does of heaven. Two, almost everything that we know about hell in the New Testament comes from the lips of Jesus. I’m just guessing that in the economy of God, people wouldn’t bear it from any other teacher. They’re not going to listen if R. C. Sproul warns them of the dreadful consequences of hell or if some other person does. People don’t believe in it even when Jesus teaches it. It’s like we’re proving the parable of the rich man and Lazarus. Dives wanted to go back and warn his brothers of the wrath that was to come. Jesus said they wouldn’t believe even if somebody came back from the dead. People just don’t want to pay any attention to it.

I ask myself this question: Why did Jesus, when he was teaching [p. 240] about the nature of hell, use the most ghastly symbols and images he could think of to describe that place? Whenever we talk about symbols or images, we use a symbol to represent a reality. The reality always exceeds in its substance what the symbol contains. If the images of the New Testament view of hell are but images and symbols, then that would mean to me that the reality is much, much worse than the literal symbols we are given.

Conversely, I would say that the good news is the marvelous images we have of heaven: streets of gold, crystal lakes, a city with buildings of precious stones. The literal fulfillment would be dazzling and wonderful, but I would think that it’s going to be incomparably greater. Again, in this case, the reality will far exceed the images that the Bible uses to communicate to us, who are limited to an earthly perspective.